Comment letter

Jun 16, 2023

Comment on Treatment of certain nonfungible tokens as collectibles

Re: IRS Notice 2023-27

To whom it may concern:

On March 21, 2023, the Treasury Department and the Internal Revenue Service ('IRS') published Notice 2023-27 (the 'Notice'), which states that the Treasury Department and the IRS intend to issue guidance relating to the treatment of certain nonfungible tokens ('NFTs') as collectibles under section 408(m) of the Internal Revenue Code (the 'Code'). The Notice requests comments on this and other issues related to NFTs, which Ava Labs, Inc. respectfully provides below.

In summary, we make three general comments regarding the Notice. First, we suggest two simple modifications to the definition of 'NFT' to reflect the inherent nature of an NFT as a tokenized representation of another right or asset that certifies ownership.

Second, we applaud the Treasury Department and the IRS for applying a look-through analysis in determining whether an NFT is a section 408(m) collectible, and provide further examples illustrating the application of the look-through approach.

And third, we recommend that, consistent with the look-through approach, an overall framework of technology neutrality should apply to matters relating to NFTs and blockchain technology in general, including revenue recognition associated with transactions that utilize them.

Background

NFTs utilize blockchain technology for various use cases, including, as relevant here, to establish and verify ownership of particular assets. In this usage, an NFT is a unique digital identifier that relates to an underlying asset. Through this unique digital identifier, the ownership of an NFT is recorded on a public ledger (i.e., a blockchain), that is secured using cryptography and other techniques. Transfers of an NFT are thereby recorded on a blockchain when an NFT is sold, traded, or exchanged.

There are numerous use cases for NFTs. For example, an NFT can establish provenance over digital art, or assets within a video game universe (such as a weapon, a treasure chest, or a plot of land within a virtual environment). An NFT might reflect ownership of a tangible asset (an NFT that represents ownership of a painting, or a particular automobile). It could represent ownership of IP – such as a musical work. An NFT might reflect a right to a particular service, such as a seat at a concert, or a right to fly on an airplane. Or it could simply act as a digital form of identification. These are but some of the ways that NFTs can be used, highlighting the impossibility of a one-size-fits-all rule for the taxation of NFTs 1.

The Oxford English Dictionary defines 'token' as 'Something that serves to indicate a fact, event, object, feeling, etc.; a sign, a symbol.' 2 This usage has been in place for over a millennium. This common and longstanding usage also applies in the context of blockchain technology, where a token is an indication or representation of something else.

Sometimes, as the Service has indicated in Notice 2014-21, a token can serve simply as a digital representation of value, i.e., as a virtual currency. However, the modifier 'nonfungible' excludes virtual currencies from NFTs. Rather, to constitute a nonfungible token (that is, an NFT), the token must be an indication of something (generally a unique right or asset) that is more than just value or the equivalent of cash.

Accordingly, we respectfully suggest modification to the Notice’s definition of NFT that we believe more accurately captures the nature of an NFT. The Notice’s definition of NFT is 'a unique digital identifier that is recorded using distributed ledger technology and may be used to certify authenticity and ownership of an associated right or asset.'

We do not think that 'a unique digital identifier' sufficiently distinguishes NFTs from other types of tokens. A token that serves as a digital representation of value (like bitcoin or ether), could have a unique digital identifier. Similarly, dollar bills (and U.S. currency of other denominations) contain unique identifiers in the form of serial numbers, but are nevertheless fungible. Therefore, we would encourage Treasury Department and the IRS to clarify that the definition of 'NFT' excludes virtual currencies – that is, tokens that are a representation of value in and of themselves – and not digital representations of other distinct assets. 3

We believe that this can be accomplished if the definition of NFT states that an NFT does (rather than 'may be used to') certify ownership of an associated right or asset. What makes a token an NFT is that it is an indication of ownership of a distinct right or asset because it is digitally unique. The look-through approach set forth in the Notice (with which we agree) is based on this premise.

Further, we do not believe that an NFT inherently is a marker of authenticity, and therefore we would recommend that the proposed definition of NFT remove the reference to authenticity. A recognized authority may provide a certification that an item is authentic—for example a respected baseball card dealer authenticating a signed baseball card. But that authentication derives from the actions and the authority of a third party rather than from the item itself. The item’s authenticity could not be sold separately and it does not itself express any ownership rights. Indeed, to the extent an NFT functions to merely tokenize the fact that an asset has been authenticated (whether by a community or by a third party), as opposed to certifying ownership of said asset, the existence of such a purely authenticating NFT should not have any tax implications.

In summary therefore, we believe that two simple modifications to the definition of NFT, as follows, would result in a more appropriate delineation of the scope of NFTs for purposes of the proposed guidance:

a unique digital identifier that is recorded using distributed ledger technology and may be is used to certify authenticity and ownership of an associated right or asset.

We note that this definition of 'NFT' could apply to certain types of tokens that perhaps could be characterized as fungible, but this should not raise concerns. Consider a tokenization of an interest in an artwork, where ten tokens are issued, each reflecting a one-tenth interest in the artwork. Or consider a tokenized ticket to a general admission concert (that lacked assigned seating). Even if these tokens did contain a unique digital identifier—it would still be reasonable to characterize, say, artwork token 2 of 10, or concert token 4 of 100, as fungible. Nevertheless, because the token certifies ownership of an associated right or asset, it should be properly characterized as an 'NFT,' despite its fungible nature.

We also note that this definition (as modified by our suggestions) is intended to address a limited question: how collectibles are treated under section 408(m) of the Code (and other sections, like section 1 of the Code, that expressly cross-reference section 408(m). Although (as we discuss more thoroughly below) we believe that a principle of technology neutrality should underlie the tax treatment of NFTs in all questions involving the taxation of NFTs, this exact definition may not necessarily be appropriate for defining 'NFT' in other tax contexts. Accordingly, we would encourage any guidance to expressly limit the application of this definition to section 408(m) of the Code.

Collectibles Guidance

We applaud the Notice’s application of a look-through approach in the context of section 408(m). While an NFT, in and of itself, does not meet any of the enumerated categories of a collectible under section 408(m)(2), we do not believe that it would be sensible to per se exclude NFTs from categorization as collectibles. It would be too easy for a person to circumvent classification of an asset as a collectible by simply tokenizing the asset.

Therefore, we agree with the Notice’s requirement that taxpayers look through to the underlying asset the ownership of which the NFT represents to determine whether it falls under the definition of collectible under section 408(m). Per the Notice, an NFT that certifies ownership of a gem is a collectible (as the underlying asset – the gem – is a collectible pursuant to section 408(m)(2)(C)). Likewise, an NFT that represents a plot of land in the metaverse is not a collectible (as the underlying asset – the plot of land in the metaverse – is not a collectible).

In fact, we believe that this is the only application of section 408(m) of the Code that is consistent with the statutory text. The items listed in section 408(m)(2)(A) through (E) are all items of tangible personal property, and section 408(m)(2)(F), authorizes Treasury to categorize 'any other tangible personal property' as a collectible (emphasis added). Indeed, to our knowledge the definition of 'collectible' in 408(m)(2) has never been applied to intangible property.

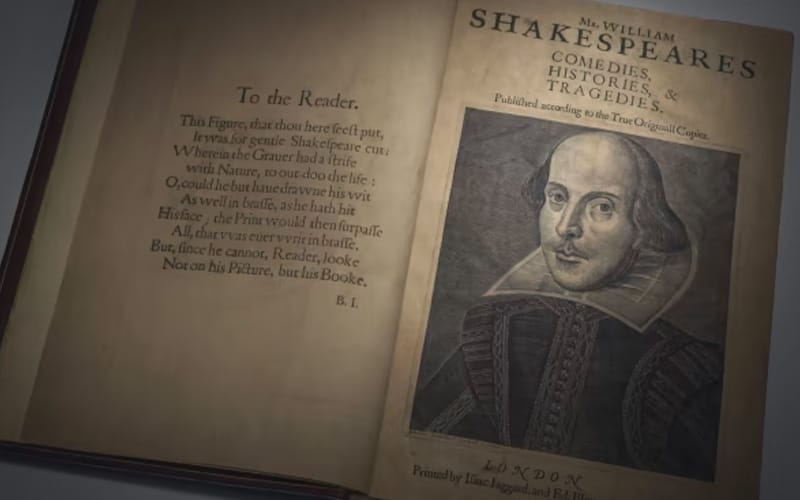

Therefore, land in the metaverse cannot be a collectible under the statute, and accordingly neither can an NFT that represents ownership of this asset be a collectible. Other types of intellectual property, such as poems, or musical compositions, or digital artwork also cannot be collectibles under the statute, and therefore neither can NFTs that represent such rights or assets be collectibles. (Although we note that tangible manifestations of such items, such as a Shakespeare First Folio, or a Beethoven manuscript, or a physical representation of digital art, likely would be collectibles, and that the classification of NFTs representing such assets should follow from the classification of the underlying asset.)

We also note that section 1(h) of the Code (which deals with tax rates as applied to collectibles) already applies a similar look through rule to partnerships. Specifically, section 1(h)(5) provides that “any gain from the sale of an interest in a partnership, S corporation, or trust which is attributable to unrealized appreciation in the value of collectibles shall be treated as gain from the sale or exchange of a collectible.” Therefore, the Notice is consistent with extant statutory authority on this issue.

Technology Neutrality and Existing Tax Law

We applaud that the Notice's look-through approach embraces the more general principle of technology neutrality. We believe that existing law should presumptively control the taxation of transactions that utilize blockchain technology. The mere fact that an asset or a transaction in respect of such asset (e.g., the exchange of a concert ticket, or the sale of a car) is tokenized and represented by an NFT should not alter the tax treatment of the transaction. The Code already tells us how to treat these transactions, and a century of tax law has been developed to fairly apply principles of taxation to these fundamental economic relationships. As a commentator has noted in this regard:

There is no change in the essential character of most assets simply because they are tokenised. New legal and/or regulatory regimes are needed only where we do not have well-defined legal and regulatory regimes for an asset and where a risk/policy assessment calls for one. 4

The federal tax law has long embraced the principle of technology neutrality. For example, the same tax treatment applies to the sale of a share of stock regardless of whether the share was issued by and recorded in a centralized database or issued through an old-school stock certificate. (The tax law might provide for different methods of identifying shares issued electronically compared to shares issued physically for purposes of determining basis and holding period, but this does not affect the basic tax principles governing the sale of stock.) Similarly, the change in form of a title of a work of art, from paper to a digital record, should not alter the tax treatment of a sale, exchange, or bequest of that work of art.

We thus encourage the Treasury Department and the IRS to specifically embrace this policy principle in its guidance, so that as new questions on the taxation of NFTs emerge, taxpayers will be encouraged to apply the law impartially. Under a principle of technology neutrality, the tax law should neither favor nor disfavor taxpayers because they utilize blockchain technology to tokenize their holdings.

We appreciate your consideration of these comments.

References

See Kappos, et al. “Fuzzy Tokens: Thinking Carefully About Technical Classification Versus Legal Classification of Cryptoassets,” BERKELEY TECH. L. J. COMMENTARIES (Mar. 1, 2023); available at: https://btlj.org/2023/03/cryptoasset-classification/

'Token' Oxford English Dictionary Online (last accessed May 16, 2023).

Commentators have suggested a similar framework be applied as a sensible classification system for crypto-assets. See Lee A. Schneider, Chambers Global Practice Guides, Fintech 2022 – Introduction, at 4-8, available at: https://drive.google.com/file/d/1v4JM8Dk4R8pi1LvZYU4pILNlIXl1jdQ1/view?usp=share_link

See Schneider, Chambers Global Practice Guides, Fintech 2022 – Introduction, at 5